Thailand’s lese-majeste law, which forbids the insult of the monarchy, is among the strictest in the world.

It has been increasingly enforced ever since the Thai military took power in 2014 in a coup, and many people have been punished with harsh jail sentences.

Critics say the military-backed government uses the law to clamp down on free speech, and the United Nations has repeatedly called on Thailand to amend it.

But the government says the law is necessary to protect the monarchy, which is widely revered in Thailand.

What exactly is this law?

Article 112 of Thailand’s criminal code says anyone who “defames, insults or threatens the king, the queen, the heir-apparent or the regent” will be punished with a jail term between three and 15 years.

This law has remained virtually unchanged since the creation of the country’s first criminal code in 1908, although the penalty was toughened in 1976.

The ruling has also been enshrined in all of Thailand’s recent constitutions, which state: “The King shall be enthroned in a position of revered worship and shall not be violated. No person shall expose the King to any sort of accusation or action.”

Thailand’s current king is Maha Vajiralongkorn

However, there is no definition of what constitutes an insult to the monarchy, and critics say this gives the authorities leeway to interpret the law in a very broad way.

Lese-majeste complaints can be filed by anyone, against anyone, and they must always be formally investigated by the police.

Those arrested can be denied bail and some are held for long periods in pre-trial detention, the UN has said.

Correspondents say trials are routinely held in closed session, often in military courts where defendants’ rights are limited.

Sasiwimon was jailed in 2015 for insulting Thailand’s monarchy

The jail penalty also applies to each charge of lese-majeste, which means that those charged with multiple offences can face extremely long jail terms.

In June 2017, a man was sentenced to 70 years in jail in the heaviest sentence ever handed down, though it was later halved when he confessed.

Why does Thailand have this law?

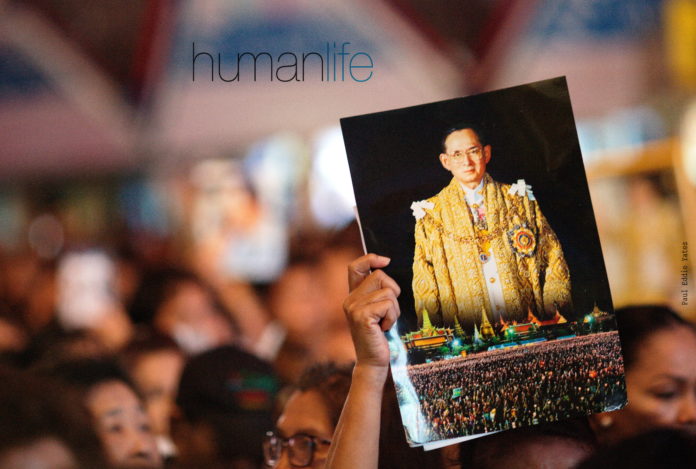

The monarch plays a central in Thai society. King Bhumibol Adulyadej, who died in October 2016 after seven decades on the throne, was widely revered and sometimes treated as a god-like figure.

He has been succeeded by his son, Maha Vajiralongkorn, who does not enjoy the same level of popularity but is still accorded a sacrosanct status in Thailand.

The military, which overthrew the civilian government in May 2014, is staunchly royalist.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha has stressed that the lese-majeste law is needed to protect the royals.

Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-ocha has warned against people making “anti-monarchist” remarks

One of the justifications for a previous military coup in 2006 was that the prime minister then, Thaksin Shinawatra, was undermining the institution of the monarchy – an allegation he vehemently denies.

How has it been used?

Though the law has been around for a long while, the number of prosecutions has risen and penalties have grown more severe since the military took power.

The UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights says the number of people investigated for lese-majeste has risen to more than double the number investigated in the previous 12 years. Only 4% of those charged in 2016 were acquitted.

There has been a wide range of offenders, from a grandfather who sent text messages deemed insulting to the queen, to a Swiss national who drunkenly spray-painted posters of the late king.

People have also been arrested for lese-majeste over online activity, such as posting images on Facebook of the late King Bhumibol’s favourite dog, and clicking the “like” button on Facebook on posts deemed offensive.

The social network in fact faced a ban in Thailand in May 2017 for failing to block illegal content including alleged lese-majeste posts, although authorities later backed off.

Activist Sulak Sivaraksa has faced multiple lese-majeste charges

Human rights groups say the government wields the law as a political tool to stifle critical speech, particularly online. The legislation, says Amnesty International, has been used to “silence peaceful dissent and jail prisoners of conscience”.

In February 2017, the UN’s special rapporteur on the promotion of opinion and expression, David Kaye, said “the fact that some forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify restrictions or penalties”.

He called for a repeal of the law, saying that “lese-majeste provisions have no place in a democratic country”.